The 35,000 MW Dream and the Indonesian Energy Trajectory

What the Jokowi era electrification efforts reveal about the factors shaping future development in Indonesia

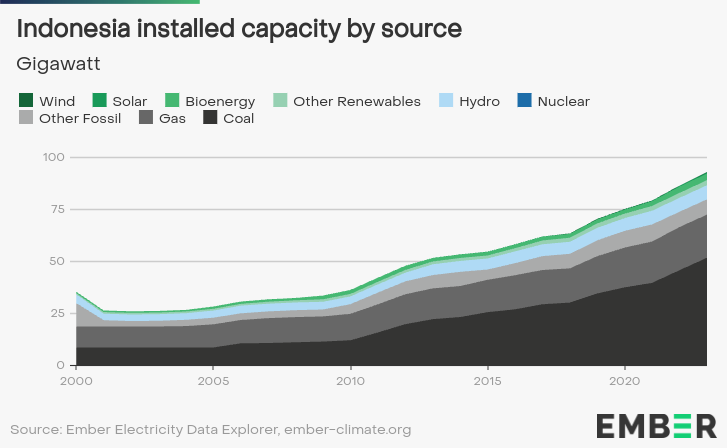

As the era of Joko Widido’s decade-long presidency ends, it is important to reflect on the foundational policy that will shape the trajectory of the rapidly developing Indonesian nation. There are many questions surrounding the future direction of the economy under the new administration, but to have any insight into the future it is important to understand the past. There is no policy more fundamental to a developing economy than infrastructure, specifically energy infrastructure, and the defining effort of early Jokowi era energy policy was his “35,000MW dream”, an effort to expand Indonesia’s electricity generation by 35GW.

For context this is equivalent to the output of roughly 15 Hoover Dams, or 8 Suralaya Power Plants, increasing electricity produced on the order of what 15 million typical Americans consume. Initially scheduled to be completed in his first term, it has ultimately taken his administration the full second term to achieve this increase in capacity.

However, understanding the implementation of a dream like this requires more detail than a simple slogan. As with all dreams, reality is never so frictionless - the challenges with Indonesian electrification are numerous. The landscape of these challenges will be decisive in channeling resources and determining what kind of projects have the momentum to make it over the finish line. Jokowi eventually succeeded in adding 35GW over the full course of his 2 terms as president, but his efforts were undeniably constrained by this landscape.

Any effort to alter the course of Indonesian energy development will have to reckon with this landscape, whether the goal is increasing access to affordable energy, mitigating the health effects of pollution, or protecting local and global environments. The implementation of Jokowi’s dream has dramatically increased power generation, but understanding the path that was taken to get there will be essential in charting the landscape of hard constraints and trade-offs that bind future government and private efforts.

To begin understanding that landscape, there are a lot of foundational questions to ask. Below are some of the key questions I have identified, along with general considerations that serve as a starting place for an answer.

Who? - Who is available to build it?

Jokowi’s initial top-line proposal called for a combination of construction from the state electrical corporation (Perusahaan Listrik Negara or PLN) totaling 10,000 MW, with the remaining 25,000MW produced from various independent power producers (IPP). Maintaining a balance between state and private efforts depends on the ability to reduce unnecessary regulatory burden for independent power production.

As one example, companies cannot enter power plant business unless they enter a power purchasing agreement (PPA) with PLN. The precedent of IPP rate cuts are a serious risk factor in justifying private investment. At the same time, there are serious efforts to pull out parts of the PLN monopoly. Proposals to introduce private power-wheeling, the sale of certain energy directly between producer and consumer, with only a fixed rental rate charged for transmission, has the potential to liberate sectors of Indonesian energy. How the contests of regulation and deregulation resolve will expand or contract the types of producers available.

The alternative to a wide range of independent producers is massive-scale, homogeneous production. In the early Jokowi electrification, the core of electrical demand was met by Chinese construction, including elements of design and operation by Chinese nationals. This approach functionally replicated the Chinese strategy of intensive coal development across Java. The question of who is in a position to fulfill various government contracts cannot be separated from the future energy environment.

How? - How can these projects be financed?

Generation is expensive, both in up-front and in operational costs. Direct state funding is an obvious option for project expenses but there is also precedent for more creative schemes at attracting project capital. The state power monopoly (PLN) has previously raised money by borrowing against optimistically reevaluated assets, with these debts implicitly backed by the state. The position of PLN within the marketplace and its relationship to the national government is fundamental to understanding these actions as the largest player in Indonesian electricity.

On the operational side, coal subsidies are currently a major factor in the profitability of current generation, with Kalimantan coal prices capped at 70 USD per tonne for state energy producers, roughly 70% of typical market prices. Understanding the incentives that motivate this type of indirect subsidy and the market distortions that follow go far in explaining the Indonesian situation.

Like with construction, the question of Chinese financing has been central to the viability of many key infrastructure projects in Indonesia. As the extent of Belt and Road lending declines across much of the world, it is important to ask whether and on what terms this lending will continue in Indonesia. This lending is bound to affect the leverage in the China-Indonesia relationship and ties Indonesian energy development decisions directly into regional geopolitics.

Also important are environmental efforts from Western countries and institutions at directing Indonesian energy development away from fossil fuels, with the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) signed at the G20 in Bali being the recent prominent example. The details of this agreement’s design and how they are translated in implementation are not self-evident. What constrains the flow of this $20 billion in financing will determine the deal's real environmental impact.

What? - What is available to build?

Coal:

In the Jokowi era, coal dominated Indonesian electrification, with 6 of the last 7 power plants that produced more than 1,000MW in the first Jokowi term being coal plants. This is the default choice for increasing total electricity in the future. Understanding its appeal will be essential in enabling compelling alternatives.

Natural gas:

Natural gas is the secondary source, responsible for the majority of the remaining national electricity. At the moment, natural gas seems to be the only other source of electricity feasible at the scale of the electricity demand. While imperfect, it is superior in addressing environmental concerns and reducing toxic particulate matter given current trends in electricity demand and coal as the default choice.

Hydropower:

Perhaps surprisingly, the largest current source of renewable energy in Indonesia is hydropower. Particularly in remote regions, high mountains, intense rainfall, and small populations often enable hydro micro-grids to ideally supply populations that lack access to national grids. It is important to many communities on a local level while bringing its own set of local environment concerns.

Geothermal energy:

By some metrics, Indonesia has 40% of the world’s geothermal potential and is placed to climb the rankings of global geothermal power generation. This share could increase as new technology and drilling techniques enter the market, successful attempts at deep, high-temperature drilling, which have the potential to be cheaper and less dependent on geological conditions. Stellae Energy is currently raising funding for proposed geothermal systems in Vanuatu, Solomon Islands and the Autonomous Region Bougainville. The market case in each of these Pacific islands is similar to that of many remote islands in Indonesia, whose only practical electricity alternatives are an expensive and vulnerable supply of diesel. Geothermal has the potential to fulfill a similar role to current Indonesian hydropower, where hydropower simply isn’t viable.

Solar and beyond:

Technological advancements are also making solar and battery systems more viable, with potential to augment or replace existing power generation, especially in remote areas. Additionally, there are a plethora of other early-stage and experiment technologies like green hydrogen, tidal energy or biomass that are being experimented with in small-scale projects across Indonesia. These may be unlikely to make a significant impact in meeting short to medium-term electricity demand and often seem designed to generate more attention than electricity. All the same, an awareness of early-stage technology uptake can prove important in understanding the incentives that will shape electricity development and investment over the longer term, regardless of the direct impact of a specific technology.

Where? - Where is it possible to build?

The Javanese-Bali grid, which connects Java, Bali, and Madura currently has the majority of the country's 80+ GW of power generation, with Java alone a majority of the Indonesian population and economy. Over the first Jokowi term, only 1 out of 7 plants providing more than 1,000 MW was constructed outside of Java. It is an open question to what extent the periphery of Indonesia will be the beneficiary of future government efforts and to what extent the government will double down on the urbanization and industrialization of the core of Java.

The Jokowi administration has gestured at moving the focus away from Java, with the New Capitol, Nusantara, an important and symbolic step. The availability of electricity will be a key component of any such efforts and the progress or delay of the capital project will have direct knock-on effects in Indonesian energy markets across Kalimantan.

The balancing act between the resources that get committed to urban, rural, and remote regions and projects will be decisive in shaping the course of Indonesian economic development, as will any decisions made to increase the coverage of the core transmission network. There are plans for expansion of the Java-Bali grid to Sumatra, and even as far as mainland Southeast Asia. The timeline for the realization of these plans will be pivotal in shaping the Indonesian energy landscape.

Why? - Why do those in power build?

Indonesia is the 3rd largest democracy in the world. The obvious pressure of holding elected office, namely the imperative of earning and retaining a maximum number of key votes, is essential to understanding development priorities. The incentives politicians face across the archipelago and within fluctuating election cycles are a vital factor in any project schedule. Along with re-election, personal financial incentives and the opportunity for various forms of rent-seeking by local actors at key decision points also guide how and where energy will be produced. No analysis is complete without understanding the stakes for those making the decisions.

Conclusion

With a new administration on the way, it is vital to look back on the challenges and success in the implementation of Jokowi’s dream to understand the future course of development in Indonesia. This has been a scattershot tour of some of the current issues I identify as essential in shaping Indonesian electrification and are some of the topics I will tackle individually and in-depth in my writing here.

If these issues are important to you, please subscribe.

If you have comments or questions, feel free to reach out to me at James.rob.larsen@gmail.com

Great article. I'm interested in understanding Indonesia's theoretical maximum potential across various renewable energy sources.

Regarding geothermal energy: You state that Indonesia may hold 40% of the world's potential geothermal capacity, approximately 25-35GW. However, I'm wondering if you could provide citations for this 40% figure? The numbers may need updating, as recent technological innovations have expanded estimated capacities. For example, the US Department of Energy now estimates ~100GW of geothermal potential in the United States alone, suggesting Indonesia's potential could be significantly higher than previously thought.

I look forward to reading more about how other renewable sources could help fill this gap.

https://www.utilitydive.com/news/doe-geothermal-generation-could-reach-60-gw-by-2050-with-tech-improvement/555948/

https://css.umich.edu/publications/factsheets/energy/geothermal-energy-factsheet

Great Piece